“Fantasy, abandoned by reason, produces impossible monsters; united with it, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of marvels”.

Francisco de Goya

In 1819 Francisco de Goya, the influential Spanish artist, was struck once again by a serious illness from which he recovered only thanks to the Madrid doctor Eugenio Garcia Arrieta.

4. Francisco de Goya, Self-portrait with Dr Arrieta, Oil on canvas, 114.62 cm × 76.52 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minnesota

Out of gratitude he painted a double portrait showing Goya on the verge of death being supported by Doctor Arrieta, offering him the medicine. In the background are some sinister figures half-hidden in the dark. This dark subject matter is later explored more deeply in The Black Paintings, a series of 14 paintings, painted directly on the walls of his new bought house between 1819 and 1823. The House was called Quinta del Sordo or The House of the deaf man.

The Black Paintings were created by the artist for his personal purposes, as internal decorations, not meant to be viewed by anybody else. This is why they were painted directly on the walls, he did not name them and also the symbolism is more obscure, since he did not need to worry about other people understanding them.

The Dog is possibly the most enigmatic of them, originally located on the upper floor, situated next to the door, lonely and abandoned.

5. Francisco Goya, The Dog, 1819–1823, Oil mural on plaster transferred to canvas, 131.5 cm × 79.3 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

It is sometimes called The Drowned Dog or The Half-submerged Dog, but like all the paintings in Quinta del Sordo they were named after Goya’s death, if Goya had a different name in mind, we will never know.

The composition is very minimal, divided horizontally in the upper and the below. The upper part is golden yellow and takes up most of the painting, the lower part is dark brown and it is just a shallow strip going up from left to right in a kind of wave. We do not know if it is a sand dune, or the sea, we would not know that it is a landscape at all if it was not for the dog in between. Same with the upper part we presume it is a sky but it might be just as well a huge rock. We can see the influence or maybe just only a parallel to Caspar Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea (1808). It is also a figure dwarfed by its surroundings, but while in Monk we can still clearly identify the land, the sea and the sky, Goya breaks away with the tradition of landscape painting and uses just colours to create a feeling.

6. Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea, 1808 or 1810, oil on canvas, 110 x 171.5 cm (Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

In the midst of it we can only see the dog’s head; his body is either buried or half-drowned. His ears are folded back and he is looking with a hopeful sad expression at someone or something outside the composition. It is amazing how much feeling could Goya convey in the expression of the dog.

7. Detail of Francisco Goya, The Dog, 1819–1823, Oil mural on plaster transferred to canvas, 131.5 cm × 79.3 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Because it is so minimal, it is also highly ambiguous. “Never before had an artist exercised such radical renunciation in order to portray solitude.”[1]

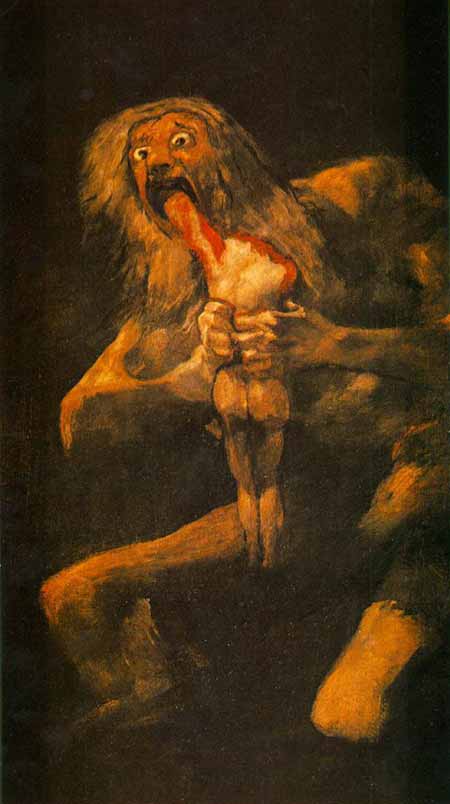

There are countless theories surrounding Goya’s The Dog. It could be seen as a futile struggle of an individual against natural forces, a reoccurring theme in Romantic paintings, and the artwork does indeed radiate a strong sense of the sublime. This is intensified by the shape of the artwork itself, it was oblong and unusually tall especially for a landscape painting, making the “sky” even more intimidating. Maybe the dog represents the artist himself, struggling to keep his head “above water” as it were, lonely and abandoned in his old age. It could be a reference to the people without a proper “master” inspired by the current political situation in Spain. We do not know what is going on, but it has a deep emotional impact on us as the viewer nevertheless. It is even more menacing than Saturn Devouring his Son, another from the Black Paintings, without being so explicit. It evokes a feeling of loneliness, hopelessness, surrender to faith and abandonment.

8. Francisco de Goya, Saturn Devouring His Son, c. 1819–1823. Oil mural transferred to canvas, 143cm x 81cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid

The dog was always a symbol for loyalty in the past, if this were true here as well, it is a loyalty betrayed. The dog is unable to move, waiting for help from outside, that will never come. An allegory maybe to the whole of humanity’s relationship to God, waiting for divine intervention, which will also never come. “God is dead”, a sentiment that starts to spread out through Europe, made famous by the German Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche decades later, although used several times before him in philosophical works.

The art historian Fred Licht has written that it is as ”essential to our understanding of the human condition in modern times as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling is to our grasp of the 16th century.”[2] We might never know the true meaning of Goya’s El Perro, but that doesn’t affect the emotional impact this painting has even after so many years. Robert Hughes says “We do not know what it means, but its pathos moves us on a level below narrative.”[3]

[1] “Web Gallery of Art, Image Collection, Virtual Museum, Searchable Database of European Fine Arts (1000-1900).” Web Gallery of Art, Image Collection, Virtual Museum, Searchable Database of European Fine Arts (1000-1900). N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.

[2] Lubow, Arthur. “The Secret of the Black Paintings.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 27 July 2003. Web. 10 Dec. 2013.

[3] Hughes, Robert, and Francisco Goya. Goya. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003. Print. PAGE 382